Most economists and financial analysts believe that central banks set interest rates.

For more than four decades, Elliott Wave International has tracked the relationship between interest rates set by the marketplace and interest rates set by the U.S. Federal Reserve and found that it’s actually the other way around–the market leads, and the Fed follows.

The latest Federal Reserve rate decision on December 19 brought the usual breathless anticipation. Confusion reigned as the U.S. president as well as a former Fed board member publicly urged the U.S. central bank not to raise rates and many wondered if the Fed would “rescue” investors with a surprise decision to leave them unchanged. The Fed, however, did what it almost always does: it brought its rate in line with market rates.

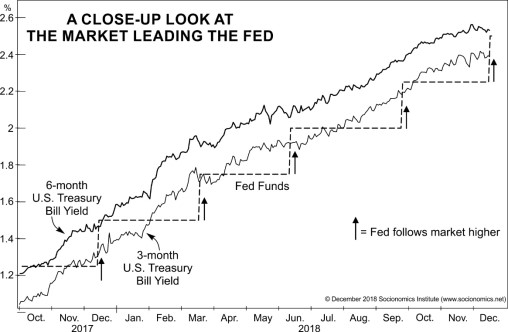

The Fed increased its federal funds rate a quarter-point from 2.25% to 2.50%. As shown by the dashed line in Figure 1, the Fed’s move followed a rise in the six-month U.S. Treasury bill yield from 2.36% to 2.56% and an increase in the three-month U.S. Treasury bill yield from 2.18% to 2.42% since the prior Fed rate hike on September 26. So, market rates remain nearly undefeated when it comes to predicting what the Fed’s actions will be.

Figure 1

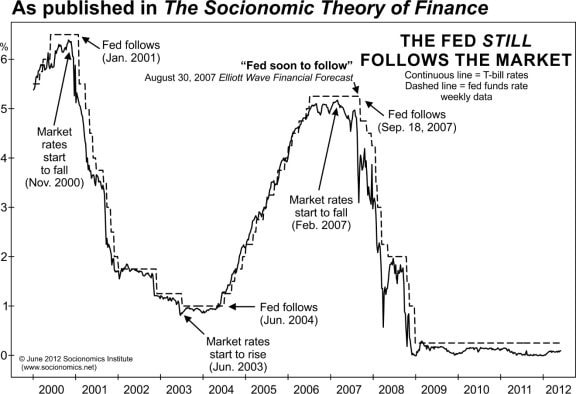

Figure 2, a longer term version of the same relationship, is from The Socionomic Theory of Finance by Robert Prechter. It shows the federal funds rate as set by the Fed and the market-set three-month U.S. Treasury bill yield back to early 2000. This history shows that the T-bill market moves first and the Fed’s interest-rate changes follow. As a result, no one monitoring the Fed’s decisions can predict when T-bill rates will change, but anyone monitoring the T-bill rate can predict when the Fed’s rates will change. We demonstrated this ability in August 2007 by predicting that the Fed was on the cusp of lowering its federal funds rate dramatically. Figure 2 shows the timing and its aftermath.

Figure 2

Over the years, Fed leaders have indicated that they’re in the dark. On September 17, 2007, a CNBC interviewer asked former chairman Alan Greenspan, “Did you keep interest rates too low for too long in 2002-2003?” Greenspan instantly responded, “The market did.” In a November speech this year, current chairman Jerome H. Powell likened the Fed’s situation to walking through a living room when the lights suddenly go out. He said, “What do you do? You slow down and you maybe go a little bit less quickly, and you feel your way more. So under uncertainty of this kind, you be careful.” The Fed has recently racked up $66.5 billion in paper losses in its bond portfolio, far exceeding its $39.1 billion in capital. Would you trust an institution that lost so much money in the bond market that it sank to a net worth of negative $27.4 billion to tell you where interest rates were headed? The Fed continually follows the market because it lacks any other useful guide.

The same principle holds in Europe, the U.K. and Australia. See chapter 3 of The Socionomic Theory of Finance for the full story of markets’ global dominance of “interest rate policy.”