If you grew up in America in the ’80s and ’90s, you’ve no doubt experienced the magic of going to the mall — a place where you could shop, meet up with friends, rent a tux for prom, grab a smoothie at the food court, go to the movies, or simply just hang out. It was a place to be.

And that’s exactly what architect Victor Gruen had in mind when he developed the plans for the first mall in the 1950s. Victor Gruen first set out to design a new shopping experience that would challenge the car-centric America that was rising. In 1956, Southdale Center in Edina, Minneapolis, opened its doors to the public. In the following decades, this new shopping phenomenon would spread all over the country and become a staple in American life.

Over the decades, the mall has seen many ups and downs. In recent years, these retail behemoths have faced challenges that would have been unthinkable in the days when developers were rushing to build the next major shopping complex in major cities across the U.S.

Social mood has always played a crucial role in the challenges that malls have faced. Shopping malls are intense centers of social interaction, and it appears that the demand for the collective experience of eating, shopping, and being entertained in a contained space is at its highest when social mood is in its strongest move to the positive.

You see this positive mood in third waves using the Elliott wave principle. These waves are usually the broadest and most robust. And chapter 31 of The Socionomic Theory of Finance says the positive mood is “characterized by investor and consumer optimism.”

When America’s first mall opened, journalists attending reflected the extreme optimism that was in play at the time. LIFE magazine called Southdale “the splashiest center in the U.S.” TIME likened it to “a pleasure dome,” and one prescient journalist said that overnight, Southdale had become “an essential part of the American way.” Thus, the timing of Southdale’s opening couldn’t have been better. Positively trending mood was fueling what the International Monetary Fund describes as “extraordinary economic growth.”

As Americans prospered, factories geared up to meet their needs. People were eager to spend their money on everything from big ticket items like homes, cars, furniture, and appliances, not to mention clothing, shoes, and everything else in between. By 1960, America’s gross national product — a measure of all goods and services produced — had climbed to $500 billion, a 150% increase over two decades. In the process, the U.S. became the most powerful nation in the world.

Thus, the introduction of the Great American Shopping Mall was right on time with the mood-driven trends in U.S. society. The cumulative total of mall openings in the U.S. rose steadily from 1956 to 1999. During this period, malls became “an institution” and a “prominent fixture in the cultural zeitgeist of suburban life.” Over those decades, malls were touted by historians and reporters as “becoming central to the nation’s culture,” “transforming the way Americans lived and worked,” and “the most distinctive product of the American postwar years.”

By the 1980s, malls had even launched brands such as Panda Express and Cinnabon. In addition, mall culture became pop culture, weaving its way into music, movies, and even television. Even Consumer Reports added malls to the list of the top 50 wonders that revolutionized consumers’ lives, along with birth control, personal computers, and antibiotics. All this reached a fever pitch by 1992, when the Mall of America opened its doors in Bloomington, Minnesota, and was the biggest mall in the USA.

But as the saying goes, what goes up must come down. By the end of the millennium, social mood and the market started shifting negatively, and malls started to take a hit. By 1999, 70 malls had shut their doors. And as the Dow Jones peaked and began its move to the downside, mall openings across America slowed down and eventually leveled out. Mall closings started to rise more and more. By 2009, there were dozens of “dead malls” across the country. And between 2010 and 2013, visits to the mall over the holiday season dropped by 50%. Three years later, 7000 retailers — many of them department stores — closed their doors. Anchor tenants like Sears and JCPenney left behind massive empty shelves at malls across the country that mall owners struggled to fill.

Today, mall properties that were once highly valued are being sold for incredibly less. Examples include Crystal Mall in Waterford, Connecticut, which was valued at $153 million in 2012 and sold in June for $9.5 million in a foreclosure auction. In Indiana, the Muncie Mall was appraised at $73 million nine years ago. It is only worth $6 million now.

Many of these “dead malls” across the country are being repurposed by developers into experimental spaces like office buildings, theaters, arcades, libraries, and apartments. For example, Northland Center outside of Detroit is having its old parking lot converted into 14 five-story buildings housing 1500 apartments, and the original store spaces will be converted into 254 lofts, along with the old Hudson’s Macy’s space being transformed into the Hudson City Market with offices, shops, and possibly a food hall. And during the next several years, Georgia Square Mall in Athens, Georgia, is slated to be converted into 70,000 square feet of commercial real estate as well as 1200 apartments, townhouses, and senior living spaces.

Considering recent trends, developers who seek to turn “dead malls” into office buildings may want to exercise caution. In May 2022, the Elliott Wave Financial Forecast observed gluts in bellwether office markets such as New York and San Francisco. And in October of last year, EWFF identified a completed five-wave rise into the Green Street Commercial Property Index, which signaled “developing weakness across the full breadth of the commercial property market.”

Developers may also want to exercise caution regarding the conversion of “dead malls” to apartments. EWFF‘s April issue said that during the past seven months, Apartment List (an apartment website), “reported that rental prices fell ‘in every metropolitan region of the U.S. as the largest batch of new housing in almost 40 years hits the markets.’” Developers seem to be betting on the continuation of positive mood, but if mood shifts and we see a waxing negative mood instead, mall properties may be sitting vacant for a while longer.

If you want to learn more about this, and socionomics as a whole, click the links in this video’s description. And if you want to see more videos like this, be sure to like, comment, and subscribe. Thank you for watching.

“I can’t believe it.” — “Who would have thought?” — “I wish I’d seen THAT coming!”

The monthly Socionomist magazine is dedicated to helping readers capitalize on social mood.

Each month, The Socionomic Institute’s analysts show you how social mood is shaping trends around the world. You spot upcoming turns and changes no one else is equipped to see coming.

Politics, business, popular culture, disease, family, religion, industry — they are all powered by social mood. The Socionomist shows you how so you can prepare for what’s ahead, take advantage of opportunities and dodge risks.

You get the magazine as part of the Socionomics Premier Membership.

How It Works

Socionomics starts with a simple observation: How people FEEL influences how they will BEHAVE.

At the Socionomics Institute, we look at how society is feeling today – so you can anticipate how society will behave tomorrow. We track social mood in real time across the globe. You’ll see how changes in social mood shift everything from the songs people want to hear to the leaders they elect; from people’s desire for peace to their hunger for scandals.

This is a rare, awe-inspiring insight. It’s what enables the Institute to help our members stay ahead of new trends that surprise almost everyone else.

Your Socionomics Premier Membership gives you this unrivaled perspective and puts you miles ahead of the herd.

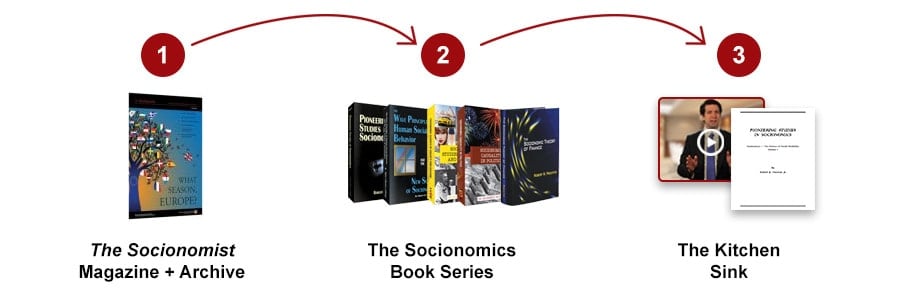

Your Path to Unleashing Socionomics in Your Life

Your Membership Resources Fall Into Three Categories:

SPECIAL OFFER

3-Month Membership Sampler

Get FULL Socionomics Premier Membership benefits for 90 days.

Price: $99

Annual Socionomics Premier Membership

Get a full year of member benefits.

Value: $1,726+

Price: $377 (Save 78%)