Recent events remind us that perhaps the greatest lesson of history is that the human species never learns the lessons of history.

As socionomists, of course, we know this to be true, with the endogenous waxing and waning of social mood being the cause of social actions. In a free and open society, the best sociometer is the stock market. But we’ve come across a data series which offers an interesting perspective.

The Bank of England has a working paper on the long-term trend in interest rates. When I say “long-term,” I mean long-term. This chart shows the level of real interest rates going back to the early 1300s.

If you want to get into the details, you can read the paper on the Bank of England’s website.

Elliott Wave International’s Murray Gunn has extracted the data from this Bank of England study to show the author’s measurement of global real interest rate, which is the average global interest rate minus the average annualized rate of change of consumer prices existing at that time.

Real interest rates are important because, as the name suggests, they reflect the real cost of investing or borrowing. If you are an investor receiving income, you want a positive real interest rate so that your income is greater than the change in the cost of living. If you are a borrower paying interest, a negative real rate is a benefit because it means that the cost of money is not keeping up with the cost of other stuff.

The first thing that jumps out from this chart is that a positive real rate of interest was the norm from the 1300s until the 1900s. Then there were two big lurches into negative real rate territory coinciding with the World Wars.

The other aspect, which the author of the Bank of England paper highlights, is that there has been a centuries’ long downward trend in the real interest rate. We’ll park that for now and instead concentrate on this observation: Major historical events have tended to occur after a rise in the real interest rate.

The rate is a seven-year average, but it is still noteworthy that turns have occurred when they did. We haven’t highlighted every blip in the rate, of course, and obviously, major historical events have occurred at many different times. However, our interest has piqued because the study seems to suggest that there could be a link between rising real interest rates and times of stress.

Let’s take a little tour across the centuries.

Throughout the 1300s, the real interest rate had been rising and peaked as the so-called Great Schism occurred, also known as the Western Schism. This was a split within the Catholic church, lasting from 1378 to 1417, in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon both claimed to be the true Pope and were joined by a third line of claimants from Pisa in 1409. The dominance of the Catholic faith made this massive geopolitical event characterized by allegiances, with the Avignon papacy being closely associated with the French monarchy. This map shows just how split Europe was at that time.

The real interest rate rebounded from its lowest point in the early 1400s and then rose quite sharply into the 1440s. This spike in the real cost of money was shortly followed by a great historical event when the Turkish Ottoman Empire captured Constantinople (now Istanbul), which was the capital of the Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire.

This was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during late antiquity and the middle ages. It had survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the fifth century A.D. and continued to exist until 1453.

The real interest rate made a low in 1527, then spiked higher into 1534. 1536 was the culmination of Henry VIII’s Reformation Parliament, when the English King was declared the head of the Church of England, breaking from the Catholic Church in Rome. This galvanized the wider reformation of religion taking place around Europe and ended the dominance of the Catholic faith.

From a low in 1620, the real interest rate rose to a peak in 1654. Interestingly, the bloody and violent English Civil War occurred from 1642 to 1651, which led to the execution of King Charles I and Oliver Cromwell becoming the Head of State as Lord Protector. In the run-ups of the famous financial calamities of John Law’s Mississippi Scheme in Paris and the South Sea Bubble in London, the real interest rate made two dramatic spikes higher. Such was the magnitude of these busts that some historians traced the origins of the French Revolution in the late 1700s to what happened in Paris many decades earlier.

The Panic of 1825 was a stock market crash that started in the Bank of England, arising in part out of speculative investments in Latin America, including the imaginary country of Poyais, a scam invented by Scotsman Gregor MacGregor, great-great nephew of the infamous Rob Roy MacGregor. The real interest rate had been rising since a low in 1792, hitting a peak on this measurement in 1821.

In the mid-1800s, the real interest rate came close to becoming negative for the first time in over 500 years. From that 1854 low just above zero, it rose nearly 5% by the 1870s. The industrial world was over leveraged, and when Austria’s Vienna Stock Market declined sharply, the Panic of 1873 set in.

Economic depression spread throughout Europe and into the United States of America, where the bank Jay Cooke and Co. went bust. North American railroad companies were devastated, a quarter of them going bankrupt. The economic slump after the Panic of 1873 was known as the Long Depression in Britain and as the Great Depression in the U.S. — that was until the 1929 stock market crash ushered in an even greater one.

Having almost touched -9% during the first World War, the real interest rate had zoomed back to positive territory and was nudging 6% by 1929. Cue the most famous crash and economic depression in history.

During the second World War, the real interest rate once again went deep into negative territory but had raised higher once more, reaching 2.6 by the 1960s. Interestingly, that preceded a very significant peak in many stock markets and economic stagnation until the 1980s. From -1% in 1976, the real interest rate rose sharply to over 5% by 1986.

The 1929 stock market crash is perhaps the most famous, but the 1987 crash is by far the most dramatic, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average declining by 22.6% on Black Monday. That’s now the equivalent to well over a 7000-point drop in one day.

So, if historical evidence suggests that a rise in interest rates precedes major events, what about now? On this metric, the real interest rate declined sharply from 1980s, but the data only goes up to 2018. Real rates in the developed world became very negative in 2021, when the consumer price inflation was accelerating. But since then, real rates have risen back to positive territory once again.

As an example, the three-month real interest rate in the U.S. was -8% in 2022 but is now back above 1.5%. Elliott Wave International’s analysis of bond yields suggests that they will be much higher for much longer, and so, we can expect real interest rates to continue to rise for the time being. And if history is anything to go by, we can expect that apocal-societal events lie ahead.

If you want to learn more about this, and socionomics as a whole, click the links in this video’s description. And if you want to see more videos like this, be sure to like, comment, and subscribe.

Thank you for watching.

“I can’t believe it.” — “Who would have thought?” —

“Did you ever think we’d see THIS?”

“This” could be anything. Radical politics. A crazy fad. Voter polarization. A sudden shift in purchasing behavior at your business. The emergence of a massive new industry. A war breaks out. Another ends in a truce.

Whatever it is, any unforeseen change in our society’s order can outrage you, shock you, awe you, present you with opportunities and risks. It can leave you searching for answers.

Well, what if you could have the answers — objective, evidence-based, well-researched answers?

That’s what Socionomics Premier Membership gives you.

How It Works

Socionomics starts with a simple observation: How people FEEL influences how they will BEHAVE.

At the Socionomics Institute, we look at how society is feeling today – so you can anticipate how society will behave tomorrow. We track social mood in real time across the globe. You’ll see how changes in social mood shift everything from the songs people want to hear to the leaders they elect; from people’s desire for peace to their hunger for scandals.

This is a rare, awe-inspiring insight. It’s what enables the Institute to help our members stay ahead of new trends that surprise almost everyone else.

Your Socionomics Premier Membership gives you this unrivaled perspective and puts you miles ahead of the herd.

Your Path to Unleashing Socionomics in Your Life

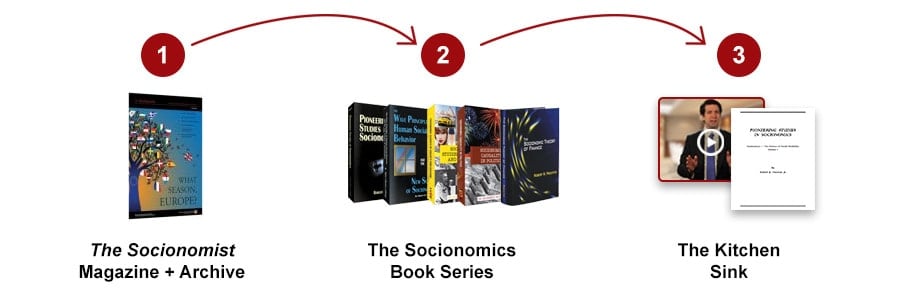

Your Membership Resources Fall Into Three Categories:

SPECIAL OFFER

3-Month Membership Sampler

Get FULL Socionomics Premier Membership benefits for 90 days.

Price: $99

Annual Socionomics Premier Membership

Get a full year of member benefits.

Value: $1,726+

Price: $377 (Save 78%)